Phoebe Watson: The Artist

Education

In January 1884, at the age of 25, Phoebe began her journey into art education. She lodged in a small room in Toronto and studied under the Scottish-born artist, William Cruikshank.[1] Cruikshank taught classes at the time as an instructor in the Ontario College of Art[2] where Phoebe was likely enlisted as a student.[3] Although there is no confirmation that she officially studied at the school, several factors support this. A letter from Phoebe dated January 1884 describes herself living next to the Normal School[4], which follows the relocation of Ontario College of Art to the “provincial educational facility, the Toronto Normal School”[5] in 1882. In addition, the letter also describes how she visited “Mr. Cruikshanks room”[6] after dinner (equivalent to modern day lunch) and was excited to attend “class”.[7] This corresponds with the times courses were offered at the school: “Fine art courses were available during mornings and afternoons to ladies and gentlemen.”[8]

The Ontario College of Art was based on the utilitarian ‘South Kensington Model’ and upheld the importance of building a strong foundation in drawing in all students. This meant a rigorous and meticulous approach to basic drawing, “no matter how uninteresting.”[9] This tedious task was not favoured by Phoebe, as indicated in a letter from a friend dated February 1884; “I do not expect you will be very long at the straight line and square business and after you commence drawing from the cast you will enjoy the work much better.”[10] Cruikshank taught cast drawing at the school and was likely part of Phoebe’s formal education. Phoebe was also likely taught life drawing (natural objects, animals, etc.), and how to use colour.[11] The school also offered classes in watercolour and oil painting, in addition to wood engraving, wood carving, china painting and other “special subjects.”[12]

As Phoebe began her “first plunge into art”[13], an overwhelming task which originally filled her with “dread”[14], she received support from her family members. For instance her brother Homer motivated her with kind words of encouragement: “just grind your teeth together and wade in.”[15] In addition, Homer offered Phoebe advice relating to her studies including a technical explanation on painting shade and tone: “A certain softness of outline is necessary for this and it is better for you to paint this edge when your background is wet.”[16]

Some sources[17] state that Phoebe was also taught by Franz Bischoff[18] in Toronto, a famous Austrian-born artist who was particularly skilled in china painting and watercolour. It is unlikely she studied with him in Toronto during the early 1880s as he immigrated to America in 1885, but he taught china painting classes in Michigan, New York and several other cities between 1892-1906 before moving to California[19]. If Phoebe did study under Bischoff, it may have taken place after her time at Toronto, perhaps in an undocumented trip to the States.

Career in the Arts

In April 1889, Phoebe received a letter from John Payne, one of Homer’s Toronto art dealers, regarding two oil paintings she had sent him. He expressed honest criticism of Phoebe’s work, explaining that although she showed “promise of something better from [her] brush”[20], her work was overdetailed and “wanting in atmosphere”[21]. He also informed Phoebe that she could not exhibit her work in the Art Union portfolio of the Ontario Society of Artists as she was not a member but offered to “get the pictures exhibited for you at the next exhibition in May.”[22] Although Phoebe did exhibit her work in Toronto following this offer, the tone of Payne’s letter and his honest comments on Phoebe’s work undoubtedly caused self-doubt for the budding artist. Phoebe later wrote about sending work to the O.S.A that year for inspection[23] and was successful. She participated in the 17th Annual OSA Exhibition, alongside her brother Homer, in the spring of 1889. Although not listed as a member, Phoebe submitted two oil landscape paintings, both at the price of $15.[24]

The little success Phoebe received during the early stages of her career caused the artist to confide her self-doubts to her brother and sister-in-law across the Atlantic Ocean. In return, they continued to show her support and encouragement.

I think with you Phoebe that actual genius will come out whether the circumstances are favorable or not… Homer says that you are not to fret that you are not making a great stir in the world. The best thing a person can do is to be true to themselves and to everybody around them and if we fall short of our aim, we will have done what we could.[25]

Despite her shortfalls, Phoebe received several portrait commissions of notable, historical and local figures during her early career. She painted six portraits of Waterloo Mayors that hung at Waterloo Town Hall, two studies of Queen Victoria which hung at the Galt bank and Rittenhouse School in Vineland, and a study of C.M. Taylor, a founder of the Mutual Life Assurance Company.[26] Her portraits of the Waterloo Mayors were a considerable commission and required a lot of work, and she was noted to have made several preliminary studies of each subject from life beforehand.[27]

1898 Historical Dinner Service

One of Phoebe’s most notable accomplishments occurred in 1898 when she contributed her talents to the Canadian Historical Dinner Service, which was presented to Lord and Lady Aberdeen in commemoration of the Lord’s retirement as Governor. The committee of the Women’s Art Association of Canada selected Phoebe as part of sixteen Canadian artists from a total of eighty-seven applications.[28] Phoebe painted twelve soup plates that depicted scenes from across Canada, including Old Mohawk Church at Brantford, scenes of Halifax, and the Chateau Ramezay in Montreal.[29] Today, the complete collection is stored at Haddo House by the National Trust for Scotland.[30] Through this experience Phoebe demonstrated her skill for detail through the intricate and delicate miniature scenes that ranged from buildings and monuments to seascapes.

Artistic Accomplishments and Mediums

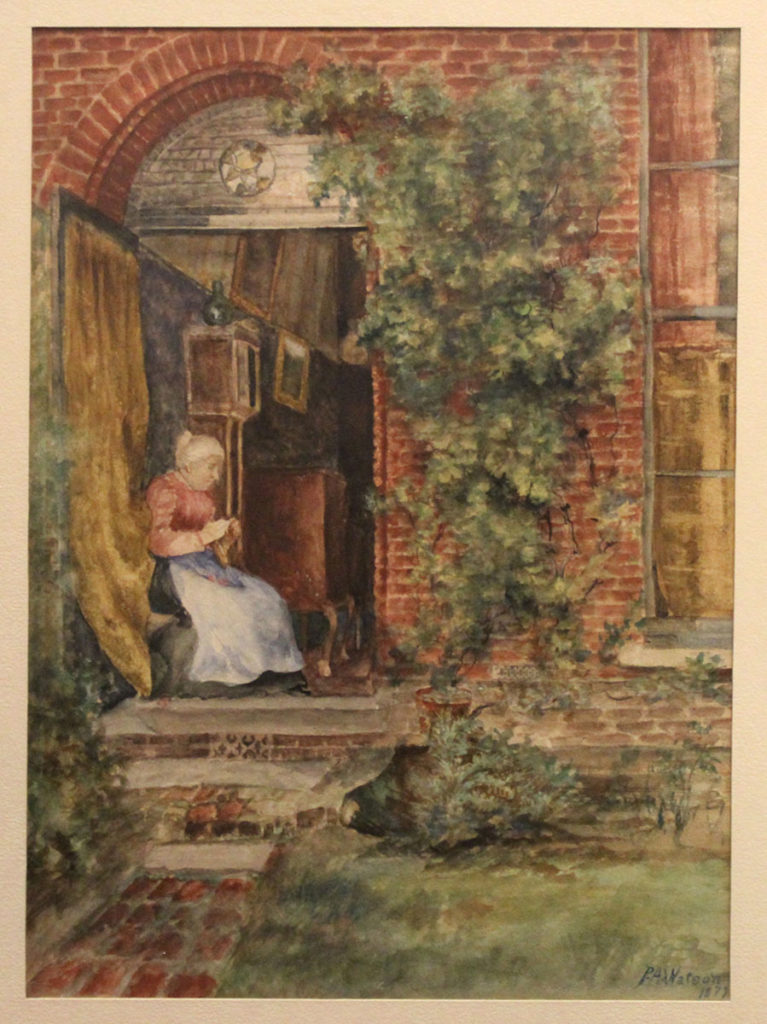

Phoebe completed several landscape paintings as well as domestic scenes of the Watson House at Doon in both oil and watercolour. Most of her landscapes featured idyllic and tranquil countryside life, painted with meticulous detail. When reviewing her artworks, it is evident Phoebe was highly skilled in watercolour and had a better command of the medium as compared to her oil paintings. Her smaller watercolour sketches exhibit a refined knowledge of colour. Her use of contrast between vivid reds and subtle pale blues to form a striking sunset against the dark silhouetted island on the horizon expertly capture the fleeting sun. Phoebe’s skill in watercolour may be attributed to her extensive work in hand-painted porcelain, as both mediums share some similarities in technique and application.

Phoebe was most known for her hand-painted china and it was likely also her preferred medium. Originally, china painting was considered a leisure activity for wealthy young women in the 1870s, and the craft also supported ideals present in the Arts and Crafts movement. The popularity of this new style in turn created a craze and as china painting was considered “socially acceptable” for women, it offered them an opportunity to pursue it as a profession and even exhibit their work.[31]

Phoebe painted a range of different pieces from “vases, urns and bowls”[32] to dinner and tea sets. Compositions in Phoebe’s china often depict scenes of nature, specifically flowers. Phoebe also used symbolism in her art and happily explained the details of her work to the guests of the Gallery.[33] Despite the large quantity of hand-painted china she created over the course of her life, most of the pieces known today are found within collections of her family members and friends.[34]

Another medium in which Phoebe often worked was pyrography, a technique she learnt during her time in England.[35] Although there is no visual record of her wood burnings, evidence suggests she worked with this style mostly at the start of her career and planned to continue her practise again in her later years.[36] Descriptions of her pyrography works include a wine-cabinet[37] and a wooden book volume that she “pricked the pictures of the late Mr. and Mrs. Watson”[38] created in the early 1900s.

Phoebe also painted a small mural over water stains on the wallpaper in her bedroom at the Watson home,[39] and recollections from visiting family describe the transformed water stain as a ‘flowering tree.”[40] Evidently, Phoebe exuded creativity and was adventurous in her approach to art. From her initial plunge to her continually developing practise and many mediums, Phoebe consistently challenged herself with the constant drive to create.

[1] Phoebe Watson, [Letter from Pheobe Watson, 18 January 1884], Homer Watson House & Gallery Archives, Kitchener

[2] William Wallace, The Encyclopedia of Canada Vol.II (Toronto: University Associates of Canada, 1948), 153-154

[3] “Sister of Painter of Doon Keeps her 83rd Birthday.” The Daily Record (Kitchener), 1941

[4] Watson, January 18 1884

[5] Daniel Payne, A mirror of curriculum: Art libraries and studio-based education: The OCAD University experience (1876 -2016) (Toronto: Self-published, 2020), 5, retrieved from http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/1357/13/Payne_Mirror_2020.pdf

[6] Watson, 18 January 1884

[7] Ibid.

[8] Harold Pearse, From Drawing To Visual Culture: A History Of Art Education In Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2014), 88

[9] Payne, A mirror of curriculum, 14

[10] Bede Dobbin (Bechtel), [Letter from Bede Dobbin, 3 April 1884], Homer Ransford Watson fonds, Queens University Archives, Kingston

[11] Pearse, From Drawing To Visual Culture, 88-89

[12] Ontario School of Art, [Prospectus, 1887], OCAD University Archives, Toronto

[13] Watson, 18 January 1884

[14] Ibid.

[15] Homer Watson, [Letter from Homer Watson, 24 January 1884], Homer Ransford Watson fonds, Queens University Archives, Kingston

[16] Homer Watson, [Letter from Homer Watson, 27 November 1884], Homer Ransford Watson fonds, Queens University Archives, Kingston

[17] A letter from a relative of Phoebe Watson references a “large vase that she did while she was studying with Bischoff” (Hardy-Payne, 1998).

[18] Ruth Russell, Women of Waterloo County, (Toronto: Natural Heritage/Natural History, 2000), 53-57

[19] Jean Stern, “Distinguished Artist Series – Franz A. Bischoff”, Tfaoi.org, 2010, https://www.tfaoi.org/distingu/fb.htm

[20] John Payne, [Letter from John Payne, 18 April 1889], Homer Watson fonds, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Roxa Watson (Bechtel), [Letter from Roxa Watson, 1 July 1889], Homer Watson fonds, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa

[24] OSA Institute, [Exhibition Catalogue, 1889], CCCA Database, CCCA PROJECTS: Artist Groups and Art Organizations, Montreal, http://ccca.concordia.ca/history/osa/

[25] Roxa Watson (Bechtel), [Letter from Roxa Watson, n.d.], Homer Watson fonds, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa

[26] The Daily Record (Kitchener), 1941

[27] Jane Van Every, With Faith, Ignorance, and Delight, (Aylesbury: Homer Watson Trust, 1967) 34

[28] The Daily Record (Kitchener), 1941

[29] Keith McLeod, “The Splendid Gift”, Antique Showcase 33, no.7 (April 1998): 49

[30] Marie Elwood “The 1897 Canadian Historical Dinner Service – A History”, Historymuseum.ca, n.d., https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/hist/cadeau/cahis01e.html

[31] Barbara Veith and Alice Frelinghuysen, “Women China Decorators”, Metmuseum.org, April 2013, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/woch/hd_woch.htm

[32] Van Every, With Faith, Ignorance, and Delight, 28

[33] Ibid.

[34] Homer Watson House & Gallery’s permanent collection and exhibition lender records indicate this.

[35] The Daily Record (Kitchener), 1941

[36] “88th Birthday Is Marked by Miss Phoebe Amelia Watson”, 1946

[37] Van Every, With Faith, Ignorance, and Delight, 28

[38] The Daily Record (Kitchener), 1941

[39] Frances McIntosh, [Notes From A Meeting With Catherine Bechtel Fromm, 1987], Homer Watson House & Gallery Archives, Kitchener

[40] Van Every, With Faith, Ignorance, and Delight, 32